2020, Mar 25

Deference and updating

Bas van Fraassen’s principle of Reflection tells you to defer to your future credences. A natural generealization of Christensen’s principle of Rational Reflection tells you to defer to whichever future credence will be rational. Elga’s principle New Rational Reflection is like Christensen’s principle, except that it allows that the rational credences may not be certain that they are rational.

Each of these deference principles is equivalent to a claim about updating—a claim about how your credences should be disposed to change when you learn that some proposition, e, is true. Reflection is equivalent to the claim that you should be disposed to update by conditioning on the proposition that your credences have been updated on e. Rational Reflection is equivalent to the claim that you should be disposed to update by conditioning on the proposition that e is your total evidence. And New Rational Reflection is equivalent to the claim that you should be disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition of propositions about what your total evidence may be.

1. Learning Dispositions

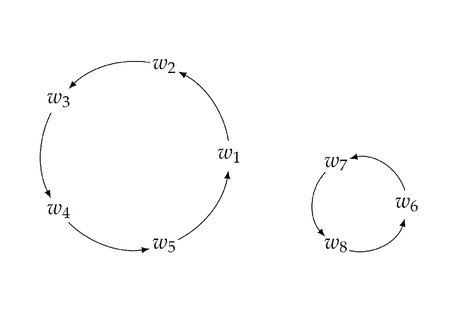

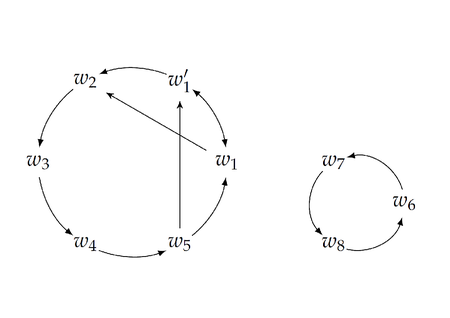

To set the stage, I’m going to suppose that you’ve got some (prior) credence function $C$, and that there’s some (finite) set of propositions, $\mathscr{E} = \{e, f, g, \dots \}$, such that exactly one of the members of the set $\mathscr{E}$ will be your total evidence. That is: for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$, $e$ might be your total evidence. And your total evidence must be some member of $\mathscr{E}$. Write ‘$\mathbf{T}e$’ for ‘your total evidence is $e$’. Then, note that, since you must learn exactly one of the propositions in the set $\mathscr{E} = \{e, f, g, \dots \}$ the set $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E} = \{ \mathbf{T}e, \mathbf{T}f, \mathbf{T} g, \dots \}$ will form a partition.

Your learning dispositions are dispositions to respond to each of these possible conditions: the condition of having t/otal evidence $e$, $\mathbf{T}e$, the condition of having total evidence $f$, $\mathbf{T}f$, and so on. I’ll write ‘$D_e$’ for the credence function that you’re disposed to adopt in the condition $\mathbf{T}e$, for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$. If you take your learning dispositions to be perfectly attuned to your potential evidence, then you’ll foresee no possibility of failing to adopt $D_e$ in the condition $\mathbf{T}e$. In that case, we needn’t distinguish the condition of you having $e$ as your total evidence and the condition of you updating on the proposition $e$. But what if you do forsee the possibility of not recognizing that $e$ is your total evidence in the condition $\mathbf{T}e$, or not responding to that total evidence by updating appropriately? What if you don’t take your learning dispositions to be perfectly attuned to your evidence? In that case, we should distinguish the condition of having $e$ as your total evidence and the condition of you updating on the total evidence $e$. I’ll use ‘$\mathbf{U}e$’ (read: you update on $e$) to stand for the condition of you taking $e$ to be your total evidence, and responding accordingly. If $D_e$ is the credence function you’re disposed to adopt when your total evidence is $e$, then $\mathbf{U}e$ says that you have taken your evidence to be $e$ and adopted the credence function $D_e$ in response. If you think that your learning dispositions are not perfectly attuned to your potential evidence, then you’ll think that, for some $e$, $\mathbf{U}e$ could be true, even when $\mathbf{T}e$ is not. Equivalently: you’ll think that, for some $e \neq f$, you might update on $f$ even when your total evidence is $e$.

2. Deference and Updating

2.1 Deference

When you defer to some other, expert, credence function, you use its probabilities to determine your own. If you’re certain of what credence function the expert has, then deference is simple: simply adopt the known expert credence function as your own. Sometimes, however, you don’t know precisely what the expert function’s credences are. In that case, you should use your credences about the expert function to determine your own credences.

Principles of expert deference tell you exactly how your credences about the expert function should determine your own credences. The simplest such expert deference principle says that, conditional on a probability function, $E$, being the expert, your credences should agree with $E$'s. That is:

Immodest Expert Deference You defer to an (immodest) expert iff, for every proposition $p$ and every probability function $E$, $$ C(p \mid E \text{ is the expert }) = E(p), \text{ if defined} $$

(Note: If $E$ is certain to not be the expert, $C(E \text{ is the expert })= 0$, then the conditional probability on the left-hand-side may not be defined; in that case, the principle will impose no constraint. That’s why I’ve written ‘if defined’ above; I’ll leave this proviso implicit in what follows.)

I’ve called this principle Immodest Expert Deference because it implies that the expert is certain to be certain that it is the expert. In the jargon, it entails that the expert is immodest. To see that this follows from the principle, just let $p$ be the proposition that $E$ is the expert. Then, the principle tells us that, for every $E$, $$ C(E \text{ is the expert } \mid E \text{ is the expert }) = E( E \text{ is the expert }) $$ If $C$ is a probability function, then the left-hand-side must equal 1, so, if you are able defer to the expert in the way this principle advises, then it must be that, for every $E$ which might be the expert, $E$ is certain that it is the expert. So you are certain that $E$ is certain that it is the expert.

Suppose you wish to defer to a modest expert: one who isn’t certain that it is the expert. The simplest such principle governing deference to such an expert says that, conditional on a probability function, $E$, being the expert, your credences should agree with $E$'s, once $E$ is conditioned on the proposition that it is the expert.

Expert Deference You defer to an expert iff, for every proposition $p$ and every probability function $E$, $$ C(p \mid E \text{ is the expert }) = E(p \mid E \text{ is the expert }) $$

This principle subsumes Immodest Expert Deference as a special case: whenever $E$ is immodest, $E(p \mid E \text{ is the expert })$ will be equal to $E(p)$. However, it applies even when $E$ may not be certain that it is the expert. If $E$ isn’t certain that it is the expert, then, when you condition your credence function on the proposition that $E$ is the expert, you’re taking something for granted that $E$ itself has not taken for granted. The solution is to have $E$ also take for granted that it is the expert (by conditioning it on the proposition that it is the expert), and only then align your credences with it. That is: the principle tells you to align your conditional credences with the expert’s conditional credences, where the condition is that it is the expert.

(By the way, there are several other options for how defer to experts. At least 12 different formulations have been floated in the literature, and there are often subtle, unexpected differences between them (see this blog post, for instance). But, in the interests of simplicity, I’m just going to focus on these two here.)

2.2 Reflection

Bas van Fraassen’s principle of reflection says that you should treat your future, posterior credence function as an (immodest) expert. That is: for each proposition $p$, given that you update your credences to the posterior function $D$, your credence that $p$ should be $D(p)$.

Reflection Conditional on $D$ being your updated credence function, your credence that $p$ should be $D(p)$ $$ C(p \mid D \text{ is your updated credence }) = D(p) $$

Suppose that you know that your updated credence function will be one of $D_e, D_f, D_g, \dots$. That is, suppose that you know your updated credence function will be one of the members of the set $\{ D_e \mid e \in \mathscr{E} \}$. Then, the claim that $D_e$ is your updated credence is just the claim that you have updated on the proposition $e$, $\mathbf{U}e$. In that case, we can re-write Reflection like this: for every proposition $p$, and every $e \in \mathscr{E}$, $$ C(p \mid \mathbf{U} e) = D_e(p) $$

Reflection has a straightforward corollary for updating: it entails that you should be disposed to update on $e$ by conditioning on the proposition $\mathbf{U}e$. To see this, instead of thinking of Reflection as a constraint on your prior credence function, $C$, think of it as a constraint on your learning dispositions, $D$. Then, it tells you that, for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$, you should be disposed, upon learning $e$, to adopt a new credence which is equal to your old credence, conditional on $\mathbf{U}e$. $$ D_e(p) = C(p \mid \mathbf{U} e) $$ (To emphasize this shift in perspective—from thinking of Reflection as a constraint on $C$ to thinking of it as a constraint on $D$, I’ve just switched the left- and right-hand sides*.) Obviously, this entailment goes both ways; so **Reflection** is equivalent to the claim that, upon learning $e$, you should be disposed to condition on $\mathbf{U}e$. (In my paper Updating for Externalists, I called this claim ‘update conditionalization’, and I showed that, given some assumptions about accuracy, update conditionalization maximizes evidentially expected accuracy. That is: if you’re an evidential decision theorist, and you want your credences to be as accurate as possible, then you should have the learning dispositions which update conditionalization recommends.)

2.3 Rational Reflection

Christensen’s Rational Reflection principle says that you should treat your current rational credence as an (immodest) expert. That is, conditional on $R$ being the rational credences for you to hold now, your credence in every proposition should be the same as $R$'s credence in that proposition.

Rational Reflection (present) Conditional on $R$ being the rational credence for you to hold, your credence in $p$ should be $R(p)$, for every proposition $p$. $$ C(p \mid R \text{ is rational } ) = R(p) $$

This formulation of Rational Reflection only says that you should defer to your currently rational credences. However, it is meant to apply at any time. So, in particular, we can think about your posterior credences, after you’ve learnt which $e \in \mathscr{E}$ is true. In that case, since you are certain that your total evidence was one of the propositions in $\mathscr{E}$, and you’re certain that $D_e$ is the rational credence function iff $e$ is your total evidence, Rational Reflection (present) says that, for each $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$,

\begin{aligned}

D_f(p \mid D_e \text{ is rational }) &= D_e(p) \\\

D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) &= D_e(p)

\end{aligned}

If you think that you should defer to your currently rational credences, you should also think that you should defer to your future rational credences. So you should also accept the following principle, govnering your prior credences, before you learn which proposition in $\mathscr{E}$ is true: conditional on $D_e$ being the rational credence function for you to hold after learning which $e \in \mathscr{E}$ is true, your credence in $p$ should be $D_e(p)$, for every proposition $p$. Since $D_e$ will be the rational credence function for you to hold iff $e$ is your total evidence, this means that, conditional on $\mathbf{T}e$, your prior credence that $p$ should be $D_e(p)$, for every proposition $p$.

Rational Reflection (future)

Conditional on $e$ being your total evidence, your credence that $p$ should be $D_e(p)$.

\begin{aligned}

C(p \mid D_e \text{ will be rational }) &= D_e(p) \\\

C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) &= D_e(p)

\end{aligned}

Once again, this deference principle implies a corollary about updating. Instead of seeing Rational Reflection (future) as a constraint on your prior credences $C$, think of it as a constraint on your learning dispositions, $D$. Then, it says that you, upon learning $e$, you should be disposed to condition on the proposition $\mathbf{T}e$, $$ D_e(p) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) $$ This update rule has been defended by Matthias Hild and Miriam Schoenfield. In Updating for Externalists, I called it ‘Schoenfield conditionalization’. Again, the reverse entailment also goes through, so the two claims are equivalent. Rational Reflection is equivalent to Schoenfield conditionalization. In Updating for Externalists, I showed that (given some assumptions about accuracy) Schoenfield conditionalization maximizes causal expected accuracy whenever you are certain that you’ll update on a proposition iff that proposition is your total evidence. That is: if you’re certain that $\mathbf{U}e \leftrightarrow \mathbf{T}e$, for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$, you’re a causal decision theorist, and you want your credences to be as accurate as possible, then you should have the learning dispositions which Schoenfield recommends.

2.4 New Rational Reflection

Because Rational Reflection tells you to treat your rational credence as an immodest expert, it entails that your rational credence is certain to be immodest. Suppose that you deny this. Suppose you’ve persuaded by authors like Williamson that you think you can end up rationally uncertain about what your total evidence is. In that case, since which credence function is rational is a function of what your total evidence is, it follows that you can end up rationally uncertain about whether your credences are in fact rational. That is: it can be rational to be less than certain that your credences are rational, even when they in fact are.

In that case, you cannot treat your rational credences as an immodest expert. So Elga recommends that you treat them as a potentially modest expert. That is: he advises that, conditional on $R$ being the rational function for you to adopt, you match your credences to $R$'s, once $R$ is conditioned on the proposition that it is the rational credence function.

New Rational Reflection (present) Conditional on $R$ being the rational credence for you to hold, your credence in $p$ should be $R$'s credence in $p$, after $R$ is conditioned on the proposition that $R$ is the rational credence function for you to hold. $$ C(p \mid R \text{ is rational } ) = R(p \mid R \text{ is rational }) $$

This formulation of New Rational Reflection says only that you should defer in this way to your currently rational credences. If we apply it to you after you’ve learnt which $e \in \mathscr{E}$ is true, then—since you’re certain that $D_e$ is the rational credence function for you to hold iff $\mathbf{T}e$ is true—New Rational Reflection (present) says that, for each $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$,

\begin{aligned}

D_f(p \mid D_e \text{ is rational }) &= D_e(p \mid D_e \text{ is rational }) \\\

D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) &= D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e)

\end{aligned}

As with Rational Reflection, there’s no need to restrict the principle to your currently rational credences. If you should treat your current rational self as an expert, then so too should you treat your future rational self as an expert. So, in particular, before you learn which proposition in $\mathscr{E}$ is true, you should satisfy the following constraint: for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$, conditional on $D_e$ being the rational posterior credence function, your credence in $p$ should be $D_e(p \mid D_e \text{ will be rational })$. Since $D_e$ will be rational iff $e$ is your total evidence, this means that, conditional on $\mathbf{T}e$, your credence that $p$ should be $D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e)$.

New Rational Reflection (future)

Conditional on $e$ being your total evidence, your credence that $p$ should be $D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e)$.

\begin{aligned}

C(p \mid D_e \text{ will be rational }) &= D_e(p \mid D_e \text{ is rational }) \\\

C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) &= D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e)

\end{aligned}

Henceforth, I’ll just call the conjunction of New Rational Reflection (present) and New Rational Reflection (future) ‘New Rational Reflection’.

Again, this deference principle is equivalent to a claim about updating. In this case, the claim is that you should be disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E} = \{ \mathbf{T}e, \mathbf{T}f, \mathbf{T}g, \dots \}$. What it is to be disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition $Q = \{ q_1, q_2, \dots, q_N \}$ is for the following to be true of your learning dispositions: for every $e \in \mathscr{E}$, there is some collection of weights $\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \dots, \lambda_N$ such that $\sum_i \lambda_i = 1$ and, for every propostion $p$, $$ D_e(p) = \sum_i C(p \mid q_i) \cdot \lambda_i $$ Or, equivalently: you are disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition $Q = \{ q_1, q_2, \dots, q_N \}$ iff, for every proposition $p$, each $e \in \mathscr{E}$, and each $q_i \in Q$, $D_e(p \mid q_i) = C(p \mid q_i)$ (if defined, of course).

Jeffrey Shift You are disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition $Q = { q_1, q_2, \dots, q_N }$ iff, for each $e \in \mathscr{E}$ and each $q_i \in Q$, $$ D_e(p \mid q_i) = C(p \mid q_i) $$

Therefore, to show that New Rational Reflection requires you to update with a Jeffrey shift on the partition $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E} = \{\mathbf{T}e \mid e \in \mathscr{E} \}$, we would have to show that it requires that, for each $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$, $$ D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) $$

We can show this easily. New Rational Reflection (present) tells us that

$$

D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}f)

$$

And New Rational Reflection (future) tells us that

$$

C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}f)

$$

Putting these two identities together gives us that

$$

D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f)

$$

So: New Rational Reflection entails that you should be disposed to update with a Jeffrey Shift on the partition $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$.

In fact, New Rational Reflection is equivalent to the claim that you should be disposed to update with a Jeffrey Shift on the partition $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$. Assume that you are disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$. Then, for any $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$, $$ (\star) \qquad \qquad D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) $$ If we let $f = e$ in ($\star$), then we get New Rational Relection (future): $$ C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) = D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) $$ If we instead swap $e$ and $f$ in ($\star$), we get: $$ D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) $$ And putting these two identities together gives us New Rational Reflection (present): $$ D_f(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) = D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}e) $$ So: New Rational Reflection is equivalent to the claim that you should be disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$.

In my paper Updating for Externalists, I pointed out that Schoenfield conditionalization (according to which $D_e(p)$ should be $C(p \mid \mathbf{T}e)$) requires a kind of immodesty that externalists should want to reject. For that rule requires you to always end up certain about what your total evidence is. Being certain about what your total evidence is means being certain about which credence function is rational. But externalists should want to say that you could be less than certain about what your total evidence is, and less than certain about which credence function is the rational one for you to adopt. Since Schoenfield conditionalization is equivalent to Rational Reflection, this was really just a re-hashing of Elga’s argument that externalists should reject Rational Reflection. And, in fact, the alternative update I recommended for externalists is closely related to Elga’s New Rational Reflection.

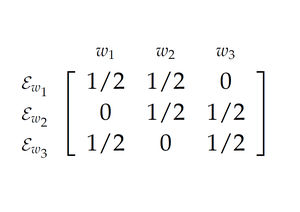

The alternative rule I recommended for externalists, called ‘externalist conditionalization’, says: $$ D_e(p) = \sum_f C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) \cdot C(\mathbf{T}f \mid \mathbf{U}e) $$ (Here, I’m summing over the $f \in \mathscr{E}$.) This is a Jeffrey shift on the partition $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$. That is, it is a rule of the form $$ D_e(p) = \sum_f C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) \cdot \lambda_f $$ where, in the case of externalist conditionalization, $\lambda_f = C(\mathbf{T}f \mid \mathbf{U}e)$.

Another, equivalent, presentation of externalist conditionalization is this: your learning dispositions should be such that:

- You are disposed to update with a Jeffrey shift on $\mathbf{T}\mathscr{E}$: that is, for every $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$, $$ D_e(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) = C(p \mid \mathbf{T}f) $$ and

- For each $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$, upon learning that $e$, you are disposed to think $\mathbf{T}f$ is as likely as you currently think it is, conditional on your updating on $e$: $$ D_e(\mathbf{T}f) = C(\mathbf{T}f \mid \mathbf{U}e) $$

What we’ve just seen is that (1) is equivalent to New Rational Reflection. So a third, equivalent presentation of externalist conditionalization is this:

Externalist Conditionalization Your learning dispositions should be such that:

- They satisfy New Rational Reflection; and

- For each $e, f \in \mathscr{E}$, upon learning that $e$, you are disposed to think $\mathbf{T}f$ is as likely as you currently think it is, conditional on your updating on $e$: $$ D_e(\mathbf{T}f) = C(\mathbf{T}f \mid \mathbf{U}e) $$